It is recommended that clinicians follow standard guidelines and screen every patient for symptoms of depression using a standardised screening instrument. Screening means asking the same questions of every patient. Many studies have shown that health professionals can be very inaccurate in the identification of depression. When a patient screens positive, this is not a diagnosis, but should be followed up with a recommendation to talk to his or her GP about their mood. [#colquhoun-dm-bunker-sj-clarke-dm-et-al,#tully-pj-higgins-r]

Questionnaires

There are several questionnaires available to assess the presence of symptoms for depression including the Beck Depression Inventory,[#beck-a-ward-c-mendelson-m-et-al.-1961] the Cardiac Depression Scale[#hare-dl-davis-cr.-1996] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.[#zigmond-as-snaith-rp.-1983] The questionnaire used may be dependent on the agency providing the service.

Screening for depression in patients with CVD

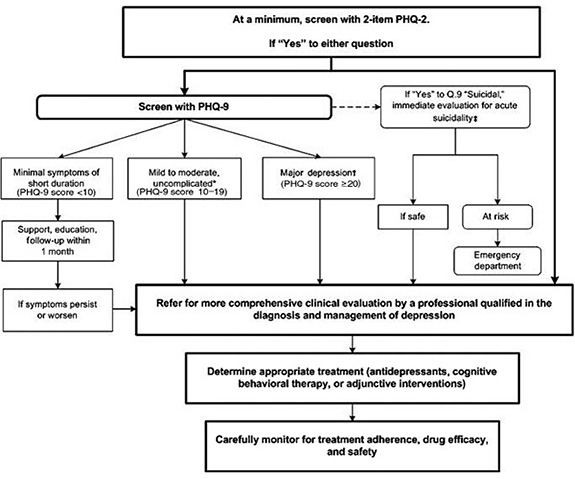

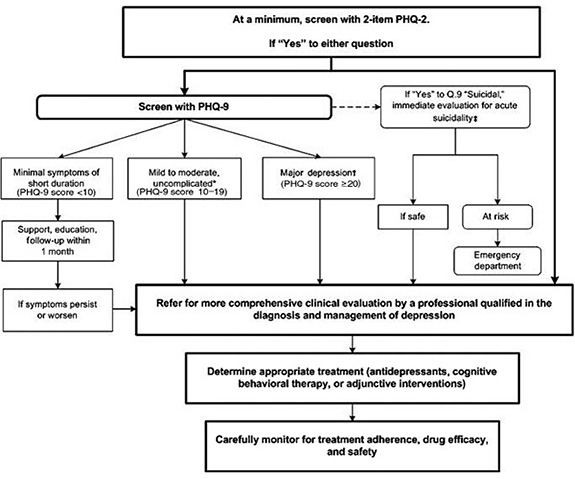

The following steps have been recommended by a number of groups on the American Heart Association Prevention Committee and have been endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association as shown in the figure below.[#lichtman-jh-bigger-jt-blumenthal-ja-et-al.-2008]. Repeated measurement of depression is recommended by the current Australian guidelines [#colquhoun-dm-bunker-sj-clarke-dm-et-al] to assist in identification of trajectories of depression symptoms.

Figure 1: Recommended steps for assessing depression[#lichtman-jh-bigger-jt-blumenthal-ja-et-al.-2008]

Patient health questionnaire (PHQ)-2 and PHQ-9 depression screen

PHQ-2 (initial screening question)

Over the past 2 weeks, have you often been bothered by any of the following?

- Little interest or pleasure in doing things

- Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless

If the answer is ‘Yes’ to either question, then refer for clinical evaluation by a professional qualified in the diagnosis and management of depression, or screen using PHQ-9.

PHQ-9

Over the past 2 weeks, have you often been bothered by any of the following?

- Little interest or pleasure in doing things

- Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless

- Trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or sleeping too much

- Feeling tired or having little energy

- Poor appetite or overeating

- Feeling bad about yourself, that you are a failure, or that you have let yourself or your family down

- Trouble concentrating on activities such as reading the newspaper or watching television

- Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed, or being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual

- Thinking that you would be better off dead or that you want to hurt yourself in some way

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and instruction manual that explains scoring and interpretation is available from phqscreeners.com. N.B. Be aware that the final item in the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 9 asks patients whether they have “thoughts that they would be better off dead or hurting themselves in some way”. Patients responding positively to this item require immediate risk assessment in line with organisational protocols.

Depression symptoms

Where a formal diagnosis is not required or available, ask about symptom patterns of various depression disorders (see www.behavenet.com).

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Treatment & Management

Treatment & Management

Exercise

Exercise

Medications

Medications

Psychosocial Issues

Psychosocial Issues

Patient Education

Patient Education

Behaviour Change

Behaviour Change

Clinical Indicators

Clinical Indicators

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Treatment & Management

Treatment & Management

Exercise

Exercise

Medications

Medications

Psychosocial Issues

Psychosocial Issues

Patient Education

Patient Education

Behaviour Change

Behaviour Change

Clinical Indicators

Clinical Indicators

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Treatment & Management

Treatment & Management

Exercise

Exercise

Medications

Medications

Psychosocial Issues

Psychosocial Issues

Patient Education

Patient Education

Behaviour Change

Behaviour Change

Clinical Indicators

Clinical Indicators